For several years I have been building a portfolio of musical works in which the physical form and external structure of specific leaf shapes and leaf arrangements are traced onto music paper. On every score, lying inside the borders of each distinctive leaf formation are hand-drawn elements of musical notation, wordings, poems, numbers and abstract shapes. These leaf pieces are extensions of my research in music composition, acoustic ecology and ecomusicology, and each one of these graphic scores holds an individual place in my personal ‘composer’ glossary of leaf morphology.

A leaf score may be viewed and performed singly or in a suite, using as many or as few pages as needed by the performer or group of performers. I do not require a site-specific space for performance, but I do encourage choosing an unconventional location with spatial properties that would be unique to live performance such as a forest or botanical garden. Regardless of how a leaf score or groups of these scores are viewed, I want to emphasize that these scores are first and foremost meant to function as intricate pieces of Graphic Music.

Graphic Music is a place where music and design will intersect in myriad ways. It functions the same way as traditional musical notation, but, uses abstract symbols, images and text to convey meaning to a performer. In my graphic leaf scores, for example, I incorporate elements of traditional notation set alongside abstract shapes, treating and bending them in unique ways. As opposed to the linear and rigid characteristics of traditional music notation, the graphic notation of my leaf works are open, offer flexibility, and constitute varieties of notations for possible worlds of sound that allows a performer to interpret these ideas. For many composers, including myself, Graphic Music continues to represent an inventive and refreshing paradigm of contemporary musical composition.

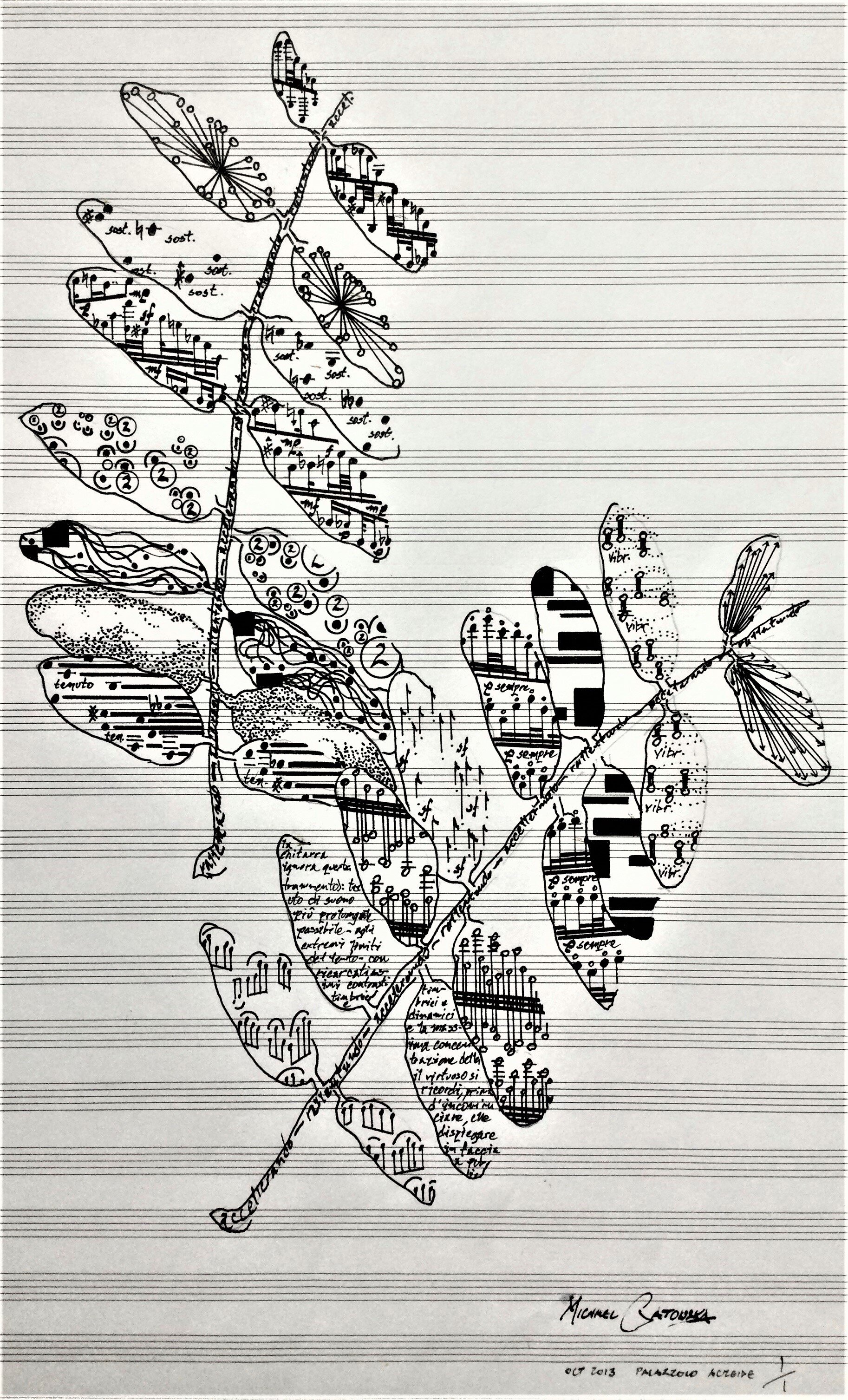

Ex.1 M. Gatonska – Eastern black oak

Having begun this project in 2012, I continue to add new leaf scores to my expanding collection of ‘musical foliage’. My primary goal is to emphasize, combine, and make connections between three fields of personal artistic interest: Music composition, soundscape studies and ecomusicology, and graphic art. Each piece may be best understood as a multi-perspectival ‘forest’, linking music, art and the natural environment. By way of this project I want each one of us to view and hear our natural environment as a musical composition, and further, since each leaf score is customarily reserved for performers, that each musician own responsibility for the creation of its sounds and silences from one performance to the next.

To make these detailed works, I first collect leaf samples during my nature walks. After a leaf has been pressed and preserved, I use it as a template to trace the outline of the leaf structure onto music paper using graphite and ink (Ex. 2). This ongoing endeavor is chiefly organized and influenced by the visual scores of John Cage, the Journals of Henry David Thoreau, the Roger Tory Peterson Identification System used in A Field Guide to Eastern Trees with its illustrations and color and black-and-white plates showing distinctive features needed for identifying species of trees, and also to some extent the philosophy of Ludwig Wittgenstein, and his far-reaching treatise Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, published in 1922.

Ex. 2 M. Gatonska – Sycamore

Even though these intricate leaf pieces are intended for improvisation and realization, and with few or no fixed rules of interpretation, each work should be regarded as a graphic construction inspired by both music and the physical forms and external structures of leaf and leaflet shapes. I want to reemphasize that 'music', in the broadest sense, is my primary subject matter of these scores.

Just as Wittgenstein tried to plot the limits of language by examining factual propositions and ‘pictures’ of facts, virtually every leaf score that I create contains two important fixed elements, one of which is more uninfringeable than the other: Namely a system of staves that surround a traced outline (or ‘borderline’) of a central leaf or leaflet structure, and the interior domain of each leaf outline where I weave graphic images of an indeterminate and improvisational nature with more traditional musical structures and notations. The staves that surround the borders of each leaf formation are intended for the convenience of a potential performer for writing down his/her realization of a particular page of the score, and these two primary elements are present in every work. However, just to prove that anything is possible, in a number of my leaf scores a violation does occur—the system of staves that surround an outlined leaf structure is absent (Ex. 3). Although I limit my material around these two basic elements, it is within the borders of each leaf shape where my whole galaxy of visual ‘arguments’ rests.

Ex. 3 M. Gatonska – Sweetgum

The staves which surround each leaf structure (Ex. 4) have an influence which is philosophical; I will discuss this element first in Staves Lying Outside a Leaf, using it as an introduction into my treatment of the Elements of My Musical Notation. In a similar manner I will discuss the significance of the traced leaf borders in The Leaf Shape Outline, since it simultaneously functions as both a perimeter and point of introduction that opens into the world where my graphic materials are manipulated. I will then briefly discuss some of the complexities of both the treatment of the elements of my musical notation and my Abstract and Graphic Shapes as a whole, and lastly I will attempt to place my leaf scores in the context of experimental music and its certain niche with tradition in My Leaf Scores and the Experimental Music Tradition.

As far as musical structure and material structure is concerned, I treat each score as if it were an adventurous piece of graphic music that mixes both the traditional with the non-traditional, not necessary reading graphic images from left to right, top to bottom or from beginning to end, but from reading each work from a variety of directions and entrance points, whether predetermined by a performer or not. Accordingly, the musical graphics will lead the musician with an aesthetic imagination to make corresponding actions and sounds. These approximate indications in my leaf scores are designed to free the interpreter from any inhibitions, and allow opportunities for a performer to discover occurrences in sound never heard before in a live performance.

Ultimately it should be strongly apparent, whether one regards my leaf scores as visual art, music or philosophical argument, that each piece was conceived the way I just described.

Ex. 4 M. Gatonska - Striped Maple

Staves Lying Outside a Leaf

The purpose of the staves that lie outside the leaf borderline is described above, but their relevance to each leaf score is also philosophical. They are not only there for the convenience of the performer, but in addition they are meant to 'represent' the interpreter in an almost metaphysical manner. The outlying staves symbolize the 'unknown' to whom I, the composer, am trying to communicate that which is distant and indefinable. They are used as a major motif in my leaf scores, and their purposeful and mysterious emptiness is intended to remind us of the final sentence of Wittgenstein's Tractatus: “What we cannot speak about we must pass over in silence”. Thus, as a composer I am now united, as it were, with the viewer/performer in this silence.

Ex. 5 M. Gatonska - Striped maple (detail)

Elements of My Musical Notation

In each leaf score I try to remain fairly economical with my choice of musical elements. Apart from the staves, noteheads are featured a great deal, hand-drawn either slightly oblique or completely circular. Pitches, determinate or indeterminate, are presented in ways that depend on the graphics. I also use neume notation and other notehead shapes such as triangles, diamonds, squares, as in Ex. 4 and the detail shown in Ex. 5, where I present a diverse array of notehead shapes. Noteheads on occasion also may include articulation and compound articulation markings such as an accent to emphasize a note or set of notes, such as staccato, marcato, pizzicato or legato indications, and bowings such as sul tasto, col legno battuto, etc. Rests in the leaf scores are used very sparingly and musical symbols such as clefs are only periodically used. Of the accidentals, I freely use flats, sharps and naturals, although accidentals in my leaf scores should not be considered as hierarchical. Of the dynamics, all are used in a range that reach from the softest volume indicated ppp towards the maximum loudness of fff, and naturally the dynamic markings will require interpretation by the performer depending on the musical/graphic context. In Ex. 4 and 5, the pp, f, and ff markings in the striped maple leaf on the right stand out in the lower middle graphic section.

I sporadically include various informational texts about trees, poems or fragments of poetic works about trees (Ex. 6), and occasionally fragments of the writings of H. D. Thoreau which may be sung, recited, whispered. For the performer I leave the entire gamut of vocal techniques open to use and to freely apply to these wordings. I also use expressive musical instructions such as cantabile, sostenuto, crescendo or decrescendo. Numbers are sometimes sparsely scattered throughout certain works’ similar to how numbers were used as easily recognizable images or emblems by Paul Klee or Jasper Johns in their paintings, although there are leaf scores that are entirely without. I periodically insert numbers as a unifying graphic element, without any hierarchical meaning.

Ex. 6 M. Gatonska – Silver maple (detail)

I think the collection of these elements expose my personal style of designing and arranging musical elements and shapes—not to mention the way by which I am able to focus the viewer/performer’s attention on my methods and techniques. The sum of these elements of music notation is treated as part of my graphic process, and they are subject to every form of treatment that I can imagine as a creator: Turned around, turned upside down, echoed, shrunken or enlarged to the point where symbolism ends and abstraction begins.

It is the hand-drawn aspect of my leaf scores that sets them apart. I substitute graphic equivalents which are in turn distorted and recombined, and my treatment of the musical elements is comprehensive, particularly considering the role of the staves lying outside each leaf. As a composer and graphic artist I hope that the subtleties of my leaf score art, as well as my personalized way of working with notation and visual shapes come across as unique, inventive and bursting with visual abundance for musicians to interpret in a live performance.

The Leaf Shape Outline

In his “Lecture on Something”, John Cage made the following provocative statement: “Every something is an echo of nothing.” Correspondingly, my leaf shapes are echoes of the silence that is represented by the empty staves that surround the traced border of each leaf. The involvement of the leaf shape in the design of each score is apparent. The traced border of a leaf identifies both the leaf and tree, and every leaf shape or leaf structure occupies a central position or arrangement on the music page. Whether arranged, juxtaposed or superimposed, every traced leaf shape serves as the entranceway from unfilled space into an imaginary 'forest' consisting of a network of hand-drawn musical symbols and graphic shapes. By crossing that temporary threshold, the performer enters the picture world of what music could be.

Ex. 7 M. Gatonska – European ash

Abstract and Graphic Shapes

I represent each leaf score using visual symbols that fall outside the realm of traditional music notation, both in combination with or instead of traditional music notation. My leaf works consist of two broadly defined categories: The first is the invention of new notation systems used to convey specific musical techniques, and the second is my use of conceptual notation such as shapes, drawings and other artistic techniques. In these particular scores of graphic music each leaf contains all the possibilities of transition from notation to graphics. These general categories are meant to be a wild profusion of graphic intention that evoke improvisation from the would-be performer.

Curves, ovals, straight and unusual lines, geometric and odd shapes, dots and areas of solid black are “all that is the case” 1 , to paraphrase Wittgenstein, given that I have restricted myself to black ink and white music paper with black staves. Shapes of various degrees of regularity, imperfection or, for that matter, recognizability are formed from these graphic elements. Similar to pitch and other musical elements, I do not treat these graphic shapes as hierarchical. In addition, and perhaps due to the limitation of my artistic ability, I do not attempt to create any feeling of depth; the whole of each leaf score is as flat on the music paper as any work by Kandinsky, Klee, Miró or Pollock, although I do employ a significant use of overlay of outlined leaf shapes. Perspective is absent in these graphic pieces.

With each leaf score creation I am not only promoting abstract notation, but I am also one of today’s many composers who are actively contributing to this form of expression and the many directions in which new music notation continues to evolve.

1 Tractu Logico-Philosophicus (in the Pears/McGuinness translation) opens in an ostensibly biblical way: 1 The world is all that is the case. 1.1 The world is the totality of facts, not of things etc.

Ex. 8 M. Gatonska – Eastern sycamore (detail)

My Leaf Scores and the Experimental Music Tradition

John Cage, Earle Brown, Silvano Bussotti, Roman Haubenstock-Ramati, and Cornelius Cardew are composers who, among many others, all demonstrate the highest artistic merit as creators of graphic or near-graphic music. Many painters have, of course, also made music the subject matter of their works. Klee's Heroic Fiddling, is an homage to his friend the German-Swiss violinist Adolph Busch, for example. Kandinsky's abstract canvasses also owe much to music; indeed his choice of a title frequently reflects this creativity (e.g. Composition No. 4, or Improvisation No. 2).

At the Notation Congress at Darmstadt in 1964, the composer György Ligeti keenly defined the distinction between symbol and drawing: The symbol has its assigned and clearly determined significance content, whereas the drawing does not. Based on Ligeti’s definition, we could surmise that the relationship between composition and interpretation can be ambiguous in musical graphics.

I do not fully agree with this conclusion. For instance, Roman Haubenstock-Ramati—who was a determined advocate of graphic music—argued that a really musical drawing is different from another drawing simply by the very fact that it will evoke musical associations. In other words, what Haubenstock-Ramati contends is that the extent to which an image suggests music is a criterion of its closeness to music, apart from the purely graphic qualities which naturally form criteria too. That being said, a painting by Kandinsky or Miró could be played by musicians. But, neither Kandinsky nor Miró paintings have been played (to the best of my knowledge) by musicians, which I think demonstrates that musical graphics are especially suited for musicians to perform since they cannot fail to evoke musical associations because they are explicitly ‘musical’.

Ex. 9 M. Gatonska – Eastern white oak

It was the great success of traditional musical notation that led composers like Cage, Brown, Bussotti, Haubenstock-Ramati and many of their contemporaries to begin to call it into question. The traditional notation had placed musicians into the role of automatically following a written notation that also served to preserve the record of the work. As a consequence, beginning in the late 1950’s these pioneering composers sought to liberate performers from the constraints of traditional notation, and to instead include them as active participants in the creation of the music. The visual richness of these scores was usually reserved for the musicians, thereby inviting them to make unexpected music that no one had planned or heard before, summoning up sounds invented purely in the performance situation and conjured up out of uncertainty and surprise interaction.

Many composers and music composition post-1945 were part of a questioning of assumptions that appeared across all of the arts in the 20th century. Painters like Jackson Pollock no longer wanted to represent real and visible objects; dramatists like Samuel Beckett who wrote plays with no story and no plot; architects like Ludwig Mies van der Rohe were building buildings with no inside or outside. Everything seemed exploratory and open-ended. Graphic notation also appeared, dewy-eyed beautiful, and many bewildered music performers were suddenly liberated. Composers had begun their query of the confining assumptions, attempting to create music with no clear plan, no guide on the page, and providing only physical elements of visual information for the performer to initiate thinking and the probing of musical and sonic boundaries.

Perhaps another dynamic as to why postmodern composers began to question traditional notation was that improvisation in classical music had pretty much disappeared. All of those virtuosic and freewheeling improvisations that were so beloved of Bach, Mozart, Beethoven and Liszt were now exactly notated on the page. A performer was supposed to perform just what was there. Graphic notation, with its orientation toward the early roots of musical notation’s suggestive rather than definitive quality, became a kind of creative opening for musicians to express themselves. By comparison with traditional notation, one of the basic ideas of musical graphics and its unusual images and shapes is to stimulate the performer to produce analogous and therefore unusual sounds. So basically what composers started to say was here is the notation, new symbols you have never seen before. We composers will not tell you what they mean, and we have left out the details so you will have to figure it out on your own. We now ask for your creative input as performers, to improvise and to determine the sonic shape of the work and to thereby grasp your right to experiment.

What I think is the most important value here, and in graphic music in general, is our collective passion for the working drawing and the tentative roughness of it, as well as its relative indeterminacy of actions and the pull of music into the visual field. It’s as if a composer is confronting this medium ‘music’ for the first time, employing any material at hand and trying to sketch it all down in order to explain it to a performer who might not be able to hear the graphic symbols in their head but who wants to recreate it.

In each of my leaf scores one can see an abundance of possibilities that display the transition from notation to graphics. However, by creating these pieces I do not want to give the impression that anything can be turned into anything else. I hope that my scores contain, as works of graphic art and also as graphic works whose chief subject matter is music, some convincing highlights.

The leaf scores are a ‘contraction into the moment’, a fantastic telescoping; they are an opportunity for the performer to dive into the richness of the creative instant. The graphics, in turn, make it possible for improvisation and all of its infinite possibilities. The action required by the performer in these scores should be animated more so by aesthetic image qualities, and to a much lesser extent by appointed notational symbols. Even though I do suggest that it may be helpful to pre-determine the performance duration of a score or group of leaf scores, I do not provide any other verbal instructions. Each piece is 11 meant to stand entirely on its own, without any instruction or form of introduction from me that may mislead or confuse the viewer/performer(s).

Thus, the musician is liberated from the strict pattern of a musical-time arrangement, and he/she is invited to participate in the compositional act. The interpreter is to be stimulated to perform spontaneous actions, and the energy of creative chance is to be set in motion. Or, one sonic idea will be combined with another. As the musician commits him/herself into ‘ownership’ a leaf score, each performance will be different and the performer will gain new appreciation for the nuances outside the notes themselves. For example, an interesting piece of graphic notation is one that was frequently performed by the violinist Yehudi Menuhin (Ex. 10). On his heavily annotated page of the Bach Sonata II for solo violin, he had scribbled all over the original score to suggest different fingerings and ways of realizing the work; these notations were made over a lifetime where this great musician had to meet this piece head-on so many times.

Ex. 10 Yehudi Menuhin’s annotated page of the J.S. Bach Sonata II

All of us want the music we compose, play, or listen to be absolute and transformative, a dynamic auditory experience that resonates through our molecules. These activities do have everything to do with one another, and John Cage certainly understood this when in he wrote in Silence: “Composing music. Performing music. Listening to music—What could these three possibly have to do with one another?” I think that what Cage is commenting on here is just how challenging it is to get performers to play for us the sounds that we composers want to hear.

Ex. 11 M. Gatonska – Bigtooth aspen

This is why music notation can become so creative. While at first it was suggestive or mnemonic, made up on any media and so varied between cultures, notation was there to help the music community remember what we need to teach orally. If notes were not there, then sphinx-like codes or strange symbols were used by composer-musicians to release the vast potential of sounds inside performers that they never knew were possible. Throughout most of music’s thousands of years of presence in human life, it was something orally taught from one person to another, and shared and invented in groups and rituals. There has always been music composition, and always improvisation, and always sounds organized by humans who brought it to life at the moment.

Ex. 12 Tibetan Buddhist Tantric score (Yang tradition)

The limit to the system of musical notation is that it will never contain all the music we imagine, play, or hear. The musical graphic can however, reach for that which cannot be explained or defined. Some of my favorite examples of graphic notation are the musical sketches of my late professor Krzysztof Penderecki (Ex. 13), because the nature of the sketch is that it develops the intact: It is a unique record of the composer's ideas, his ardor and vibrations of the spirit, investigations and deletions. They provide entries into an unknown and huge architectural structure, full of an unusual diversity of material, volatility of signs, colors and techniques.

Ex. 13 K. Penderecki – sketch for Jutrznia

My leaf scores contain and strongly resemble exhaustive arguments in graphic terms, whereby I am either trying to reduce an argument to its most basic components, or endeavoring to assemble whole complexes of multiple forms. I understand that this complexity, as well as the difficulty of making any single logical code of 'translation' from graphics to sound can be obscure. Especially since musical notation itself is part of a complicated interplay of forces that can thoroughly inhibit a performer from attempting to 'realize' even a small section of a leaf score. Still, I hope that an interpreter can appreciate a leaf score, stemming not from a regard for it as a piece of experimental music, but from a fascination with its visual dexterity and my attempt at creating an entirely logical world of 'visual' musical imagery—an imagery which seems to say everything 'about' music, but none of which is music.

Ex. 14 M. Gatonska – Sassafras

Ex. 15 M. Gatonska – Red oak

For every composer, the musical sketch is equivalent to a graphic presentation of acoustic events developing in his imagination. These rough first-attempts also reveal the emotional insides of the composer and the freshness of ‘being in the creative moment’. I believe the best music is so much more than any one performance or musical image—it is the music that contains the freely swirling motion of eddies from inside our heads, and that finds its way out into the world by way of an eternal scrawling and unstoppable flow…

______

For more information please contact Dr. Michael Gatonska

MICHAEL GATONSKA is a composer and soundscape artist. He is a recipient of a Civitella Ranieri Fellowship, Kosciuszko Foundation Fellowship, Akrai Fellowship, MacDowell Fellowship, and multiple awards from New Music USA and ASCAP. His music has been recognized through commissions and awards from arts institutions including the Hoeschler Foundation, Roberts Foundation, Mary Cary Flagler Charitable Trust, Puffin Foundation, MATA, Paul Underwood/ACO commission, Chicago Symphony First Hearing Award and the American Prize. He has collaborated with orchestras and ensembles including the Minnesota Orchestra, the Cabrillo Festival Orchestra, Pacific Symphony, Hartford Symphony, String Orchestra of New York City, Talea, Sinfonietta Cracovia and the Chicago Chamber Players.

Gatonska has received degrees from Manhattanville College, the Academy of Music in Kraków, the Manhattan School of Music and his DMA from Fryderyk Chopin University of Music in Warsaw. He has served as a member of the composition faculty at the Pontifical Xavierian University in Bogotá, Colombia.